Overview: Price Inflation Creation

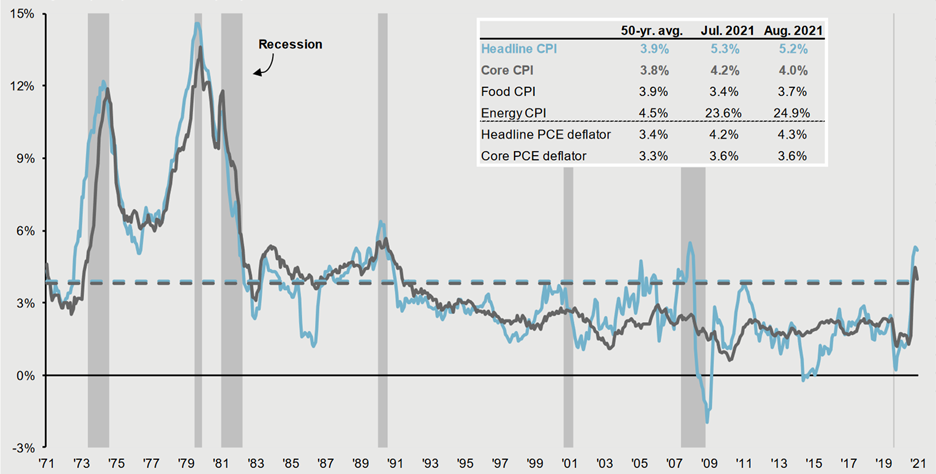

COVID has caused worldwide economic upheaval since the pandemic began and continues to do so. Global economies have struggled to adjust to the many kinks COVID has created in supply chains, and virtually every industry has been affected. As shown in Figure 1, the inflation caused by rising demand, disrupted supply chains, and government policy is evident in the US Consumer Price Index, which pegs overall price inflation in the US at 5.2%; this inflation rate is the highest seen since America was in the throes of an economic recession in 2008 and are 1.3% above the average headline CPI over the past 50 years. Much of this price inflation the result of the product scarcity caused by pent-up demand, global worker shortages, tight raw materials supplies, and supply chain chaos as COVID restrictions ease.

Figure 1: U.S. Consumer Price Index and Core Consumer Price Index

(% change vs. year prior, seasonally adjusted)

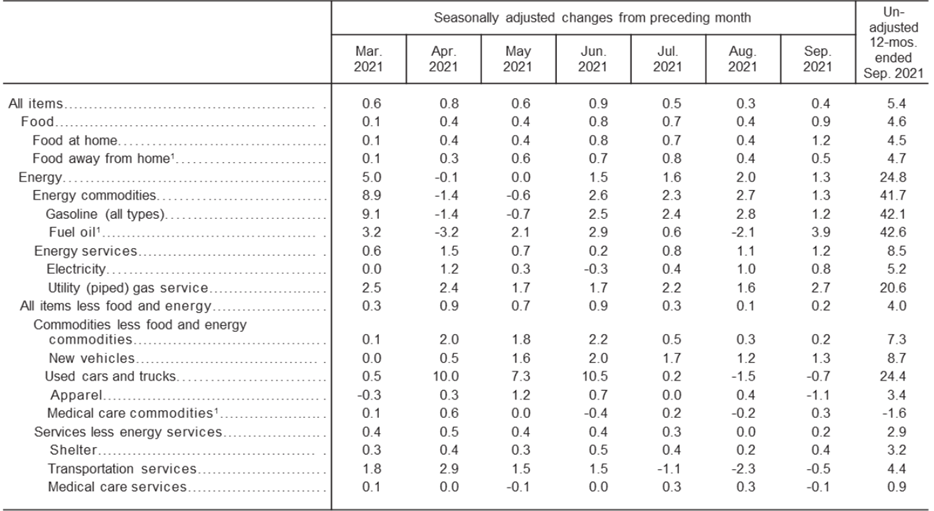

Figure 2 shows the itemized percent changes in prices in cities throughout the United States. As you can see, many industries have posted drastic price increases. In the US Urban CPI, Only the Apparel, Medical Care Commodities, Shelter (Less Energy Services), and Medical Care Services (Less Energy Services) Industries have seen year on year price increases below the United States’ 50-year average CPI of 3.9%. All other industries saw greater increases, with inflation of more than 20% in the Used Car and Truck and Utility (Piped) Gas Service industries, as well as in the Energy Industry overall. Even greater inflation can be seen in the energy commodities industries; both the Gasoline (All Types) Industry and the Fuel (Oil) Industry saw price inflation of over 40% over the past year. The extreme inflation rates currently being experienced across the board are an economic symptom of the COVID-19 pandemic. However, as COVID transitions from pandemic to endemic, the key question is, “will inflation do the same?” as demands for higher wages work their way through the system.

Reduced buying power as wages have not kept pace with inflation, along with the reluctance of many employees to return to work and the resultant demands for better working conditions and terms, have led to a global strike wave that is contributing to the worker shortage in the near term, and could contribute to higher inflation over the longer term.

Figure 2: Percent Changes in Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers (CPI-U): U.S. City Average

So many strikes occurred in October in the United States that many news outlets took to calling the month “Striketober”. More than 100,000 workers in the US were so dissatisfied with their current working conditions that they decided to band together and fight for better treatment (“100,000 Workers Take Action as ‘Striketober’ Hits the US”, Daniel Thomas, BBC.com) (‘Our Future Is Not For Sale’: America Is Witnessing the Biggest Strike Wave in a Generation”, Lauren Kaori Gurley, VICE.com). Over the course of October, in the US alone:

- Over 10,000 John Deere workers went on strike over pay and conditions.

- Over 60,000 television and media workers threatened to strike, although resolution was reached beforehand.

- Over 24,000 Kaiser Permanente workers in California and Oregon authorized a strike due to pay and working conditions.

- 1,400 Kellogg factory workers went on strike in Michigan.

- 2,000 New York hospital workers went on strike.

- 700 Nurses in Massachusetts went on strike.

- Whiskey makers, coal miners, steel workers, grad students, and bus drivers are also poised to strike, should they not receive wages that have been adjusted for inflation soon.

This massive amount of worker dissatisfaction, paired with many companies’ aversion to inflation-adjusting wages, has contributed even further to the worker shortage caused by the pandemic.

Outside the United States workers striking due to job dissatisfaction is evident as well; in South Korea over 550,000 people went on strike last month with some rallies reaching populations of 27,000 or more people, effectively shutting down large swathes of the country (“Labor Union Stages Rallies, Strikes in South Korea”, Chang May Choon, straitstimes.com). If these strike waves continue, and companies do not begin offering employees higher compensation, it is likely that the future will only hold further supply chain disruptions. This will be in addition to the disruptions directly associated with the pandemic, creating an even greater and ever growing, rift between pre-pandemic ‘normalcy’ and the inflation-filled reality we currently find ourselves experiencing.

Main Risks – No Supplies, No Workers:

- Inflation has risen drastically over the course of 2021.

- Pandemic-caused worker shortages are putting strain on supply chains globally, contributing price inflation for many goods.

- Labor strikes, both in the US and internationally, are putting pressure on companies to improve wages and working conditions, lest they wish to attempt functioning without critical portions of their respective workforces.

Looking Ahead – Automation and Consolidation

- It is likely that price inflation will continue to increase as pandemic-related worker shortages do not remain fully addressed and many countries still deal with pandemic related difficulties.

- This will likely increase worker dissatisfaction, as people continue making their previously held wages and become unable to fully support their lifestyle.

- This will likely lead to further worker shortages in certain industries as workers “trade-up”, strike, or quit due to lack of fair pay, or business downsizing as companies struggle to pay their employees more without a reliable supply of raw materials.

- It is likely that soon many companies will be seen automating human processes to save money or downsizing their business to supply employees with fair working conditions.